A few weeks ago, a reader asked if I could add some discussion and analysis about cloud cover in Alaska, and its relationship to high and low pressure systems. I decided to look at this using ERA5 reanalysis data, because it's easily accessible and should have reasonably good quality, being constrained by satellite measurements.

The first thing to glance at is the climatological normal for cloud cover, at least according to the model. Here's the ERA5 estimate of the annual mean percentage of sky that's covered by cloud at any height above ground (click to enlarge):

Not surprisingly, the cloudiest regions are the Aleutians and southwestern Alaska, Southeast Alaska, and the northern North Slope. It also makes sense that the northern interior is the least cloudy part of the state, as it's relatively far removed from the storm-frequented Aleutian region and is also sheltered from Arctic storminess. I'm not sure I would have guessed, though, that northwestern Alaska to the south of the Brooks Range has as little cloud as the much more continental zone in interior northeastern Alaska.

The seasonal breakdown is striking - see maps below for January, April, July, and October. Much could be said on this, but I'll just note the relatively high proportion of clear skies across the interior in winter (good for aurora-gazing!); and obviously late winter and early spring have the clearest skies for most, being also the driest time of year for all of the state except the maritime south (where early summer is drier). Also - summer is relatively (some would say dreadfully) cloudy for most of southern Alaska.

A wider view of the high-latitude Northern Hemisphere shows that interior Alaska has some of the clearest skies of any sub-Arctic location in January. With long hours of darkness, this makes Fairbanks a top international destination for aurora seekers. In contrast, notice how very cloudy western (and indeed most of) Russia is.

For completeness, here are the other months, and the annual average, for the high-latitude hemisphere.

Russia does much better than Alaska for sunshine in summer, and in fact it has a dramatically more pronounced seasonal cycle of cloudiness. This is completely new to me, and I'll have to think about why this is.

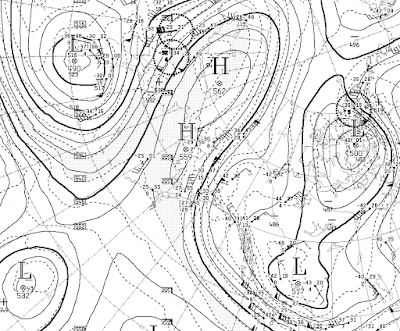

I'll pick up this thread in another post, looking at the relationship between pressure patterns and cloud cover for different parts of Alaska.

Happy New Year to all!