Objective Comments and Analysis - All Science, No Politics

Primary Author Richard James

2010-2013 Author Rick Thoman

Monday, August 26, 2024

Another Landslide

Thursday, August 22, 2024

Ex-Typhoon Ampil

The third major storm in less than a week affected western Alaska yesterday, courtesy of the remnant circulation of Typhoon Ampil. The low pressure center came in a bit farther north than the previous two storms, but high winds were widespread across the western coastline and hills.

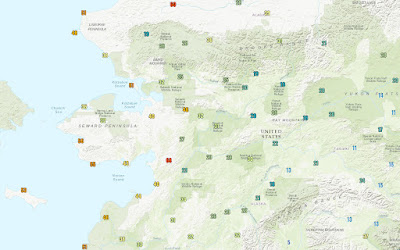

Here's the MSLP analysis from 4pm AKDT yesterday, courtesy of Environment Canada:

The wind gusted to 55 mph in Nome in the early evening, and the peak sustained wind of 41 mph ties the Nome record for August, set back in 1949. To find a stronger storm in early autumn, we have to look to the first week of September, when 44 mph sustained winds were measured in 1964. (But instrumentation is different nowadays, so it's not really a fair comparison. In recent years the most comparable event was August 24, 2012, with 37 mph.)

Here are some of the peak wind gusts around the region yesterday (in mph):

Although this is the 3rd storm in quick succession, it's actually the 4th storm to hit the west coast in the past two weeks (I missed the first one in my previous post). Here's the MSLP analysis from the afternoon of August 10: this one came in much farther south.

The 14-day precipitation is 2-4 times normal across much of the west and northwest, and the anomaly pattern is extremely similar to the July outcome - except for Southeast, where it's been much drier lately.

Tuesday, August 20, 2024

Heat and Floods

Saturday, August 17, 2024

Persistence

Continuing with July's theme of wet weather, western and southern parts of Alaska (except Southeast) have remained much wetter than normal so far this month. Here's a "percent of normal" analysis based on NWS precipitation estimates for the latest available 14-day period. Flood watches and warnings are out for several regions in the west.

The wet pattern illustrates the idea that weather patterns often tend to persist for weeks or even months, but as we saw earlier in the summer, a dramatic reversal can occur too:

Thinking about this, I started wondering if weather patterns have become more or less "persistent" over the decades in Alaska. A simple measure of persistence can be constructed by counting the frequency with which the precipitation (or temperature, wind etc) departure from normal reverses sign from month to month.

For example, if the pattern flips from warm to cold and back again every month of the year, then this persistence index is zero: the monthly anomalies have opposite signs in consecutive months. But if all 12 months are warmer than normal, then the index is 100%: no sign reversals occurred between consecutive months.

Using statewide data from NOAA/NCEI, and using a trailing 30-year mean as "normal", the result looks like this:

Higher numbers correspond to more month-to-month persistence. The first thing that strikes me here is how non-persistent statewide temperatures are; I would have expected higher persistence for temperature, given the large influence of nearby (and very persistent) ocean temperature anomalies on Alaska climate. But having said that, the atmospheric circulation pattern governs a very large fraction of the temperature variability from month to month, so perhaps it shouldn't be surprising.

It's also interesting to see that persistence was relatively low for both temperature and precipitation in around 2005-2015 (the chart uses a 10-year running average), but temperature persistence has increased substantially in recent years.

The recent prevalence of month-to-month persistence is partly related to the sharp uptrend in statewide temperatures: if it's "warm all the time", then the persistence index will be high. However, it's worth noting that the sharp increase in temperatures in the 1980s did not produce an equally dramatic rise in temperature persistence. Here's a chart of actual decadal temperatures and precipitation; both have increased over the last 75 years.

To counter the effects of trend on the persistence index, it seems worthwhile to detrend the data. After doing this with a simple linear trend (calculated for each month of the year separately), the persistence index looks like this:

Saturday, August 10, 2024

July Climate Data

Last month was the wettest July in recorded climate history for Alaska (1925-present), with a statewide average precipitation of 5.2 inches, according to NOAA/NCEI. The previous record was 4.8" in 1959.

The contrast with June was dramatic, as June was tied for 3rd driest on record statewide.

As we would expect, the flow was more westerly than normal over most of Alaska, courtesy of above-normal pressure near and south of the Aleutians, and an unusually strong trough over the Arctic Ocean (nearly opposite to the June pattern). The maps below show the 500mb height and 850mb westerly wind anomalies for the month.

Wednesday, August 7, 2024

Sleet in Summertime?! North Slope Unusual Summer Weather.

North Slope Mike here. Summertime is busy time in Alaska. While we are actively fishing, hunting, camping and enjoying the great outdoors the weather is equally active and can vary drastically over just a few days. As Rick talked about, yesterday the North Slope was bathed in record heat courtesy of strong southerly flow packed between a strong Bearing Sea trough and a large ridge parked over Eastern Canada,

However, the topic of this post is about unusual cold weather occurring rather recently this summer. In particular the night of July 27-July 28th of 2024 was quite exciting. I am a few days behind the weather in the writing about this and I apologize. If we rewind the weather about a week to 8/1/24 areas on the eastern north slope received accumulating snowfall. Snowfall in summer is fairly common, in fact Utqiagvik (formally Barrow) has seen as much as 4 inches of snow in the August of 1969.

So, if it is cold enough at times in summer for snow to fall, what about sleet? The difference between snow and sleet has to do with temperature dynamics in the lower atmosphere. While a wet, slushy snow intuitively seems quite probable in summer, sleet however seems rather impossible. See the definitions for both (courtesy of NOAA):

Snow. Most precipitation that forms in wintertime clouds starts out as snow because the top layer of the storm is usually cold enough to create snowflakes. Snowflakes are just collections of ice crystals that cling to each other as they fall toward the ground. Precipitation continues to fall as snow when the temperature remains at or below 32 degrees F from the cloud base to the ground.

Sleet occurs when snowflakes only partially melt

when they fall through a shallow layer of warm air. These slushy drops refreeze

as they next fall through a deep layer of freezing air above the surface, and

eventually reach the ground as frozen rain drops that bounce on impact.

Depending on the intensity and duration, sleet can accumulate on the ground

much like snow.

As you can see snowfall requires the entire air column in the lower atmosphere to be "cold" or below freezing. The lower 1000' of the air column can be a few degrees above freezing and thus the observer in this case will see wet, slushy snow instead. Sleet requires a narrow wedge of warmer above freezing air aloft to melt the snowflakes and then a relatively thick layer of subfreezing air to freeze the droplets into ice pellets. I've discussed this with the folks at the National Weather service in Fairbanks and they tell me sleet in general is very uncommon for northern Alaska and is almost unheard of in summertime! This intuitively make sense as the majority of "wintery" precipitation occurs in airmasses that are well below freezing throughout the air column. Freezing rain is more common in spring and summer as the marine inversion layer over the slope is relatively shallow.

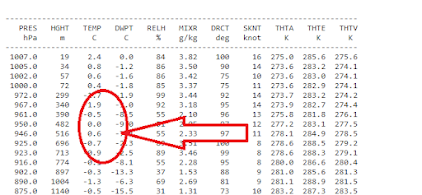

On July 27th, 2024, rain turned to sleet in coastal areas of the north slope. This observer is in Kaktovik and reported sleet to the NWS at 1800 hours that night. Jason Ahsenmacher of the Fairbanks NWS verified my observations and said that the forecast models suggested the possibility of sleet occurring. He was quite excited by my observation and provided me with the following meteogram. Note, it also hinted at the snowfall Kaktovik ended up seeing on the 1st.

Looking at the nearest temperature soundings in Utqiagvik at that time shows a narrow above freezing layer on top of a "colder" subfreezing layer above the ground. However, keep in mind that this observation was taken 500 miles away from Kaktovik and it serves to illustrate the warm wedge. Had this same temperature profile been over Kaktovik at that time the sleet would have been snow due to evaporative cooling. You can see the small above freezing wedge of warm air above the subfreezing air layer below it. There was about 1300' of sub-freezing air below the warm wedge. I even took a photograph for records and submitted it to the NWS. This sleet was bouncing off my 4-wheeler when it was falling.I'd like to thank both Jason Ahsenmacher and Bobby from the Fairbanks NWS for their correspondence and assistance on this post. Indeed, I'd be curious to see how often sleet occurs in summertime in Alaska. Mike.