Hi, Rick T. here with a post about Fairbanks summer rainfall.

I was at a meeting a few weeks ago and one of the folks there, who works in community planning, was wondering if Fairbanks summers are becoming wetter. After all, the past five years (especially 2014 and 2016) have featured two of the wettest summers of record. If summers are getting wetter, that is something that planners need to take into account when considering things like downtown storm drainage capacity, rural road culvert sizing or generally higher river levels. Happily, here in Fairbanks we have enough historical data to take a stab at answering that question.

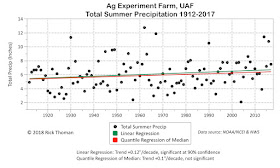

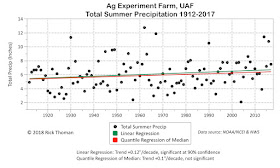

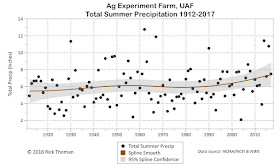

Since summer precipitation often comes in the form of showers and thunderstorms (especially the first half of summer) and these are much less frequent (climatologically speaking) over the flats as compared to areas closer to higher terrain, it's not a good idea to use the usual Fairbanks "threaded" climate record, since we know that the Fairbanks Airport, being out on the flats, receives significantly less rain than areas not far to the north and east. Luckily, we have precipitation observations taken in almost the exact same place, from the UAF Ag Farm, since July 1911. While there are some data quality problems with the Ag Farm observations over the decades, summer precipitation looks reasonable. Amazingly, there appears to be only one month that is actually missing, August 1969. For this one month I used the College Observatory data (taken on West Ridge near what is now called Jack Townshend Point, about 3/4 of a mile northeast of the Ag Farm). Here is scatter plot of the accumulated June through August precipitation at the Ag Farm for the past 106 years (1912 through 2017):

Just glancing at the graphic there is nothing obvious to my eye. The ten wettest and driest years are not all bunched-up on one or the other side of the plot. Naturally, there is some clustering: the 1920s saw a number of very dry summers and the 1940s several wet summers. Of course, we need not rely on our eyeballs; statistical analysis is our friend.

The simplest analysis is just linear regression. In the chart above I've plotted the observations along with ordinary linear regression (green line), which in effect is modeling the average (mean), and a technique called linear quantile regression, which here I use to model the median. A reason to check both is that ordinary linear regression is sensitive to individual values that are far from other values (i.e. "outliers"), while quantile regression of the median is not sensitive to extremes. In this case, we see that both flavors of linear regression show an increase of about an inch precipitation over the past century. For the ordinary linear regression this is significant at the 90% confidence level but not at the 95% level. The trend of the median summer precipitation is not significant at even the 90% level.

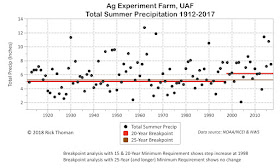

Of course, it's entirely possible (even likely) that changes in summer precipitation are not best described by a simple linear fit. Often in Alaska, a piecewise linear regression (i.e. "hockey stick") provides a better estimate of trend – but not in this case. There is no evidence of any significant changes in the linear trend.

Another change we can check for are any abrupt "step" increases. When we do this, the results are also mixed:

Here, the results are mostly dependent on the required length of any segment. Since we are looking a long term changes that might be important for community planning, I restricted the analysis to changes that persist at least couple of decades. Requiring a minimum length of 20 years shows one step increase, at 1998 (note: the analysis was not restricted to a single step change. With 106 years of data, as many as five step changes are possible). Interestingly, increasing the minimum length to 25 years results in no step changes of statistical significance.

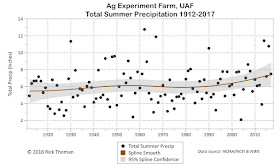

The last analysis I'll look at here is a simple smoothing of the observed precipitation:

Here the brown line is a cubic spline fit to the data. Cubic splines are very commonly used to detect patterns (not just linear) in noisy data. In this case, looking only at the brown line, we see, much like the linear regression analysis, a general upward trend, especially since the 1990s, with a total increase of nearly two inches between 1912 and 2017. However, this is only part of the analysis. Since we don't know what the hypothetical "true" fit is, in this case primarily due to the spread in the summer to summer rainfall, we can construct confidence intervals that give us a better idea of where the actual (but unknown) fit lies. I've done that here, shown as the gray shading. Notice that the confidence interval at least partially overlaps itself for the full 106 years of records, e.g. look along the total precipitation 6" grid line. This suggests that we don't (quite) have high confidence that there really is a significant change in the spline fit.

So where does this leave us as to the original question? Are summers becoming wetter? It looks to me like the answer is an unequivocal "maybe".

On the

yes side, the ordinary linear regression trend is significant at the 90% level, as is the 20-year minimum length step change.

On the

no side, the trend of the median summer precipitation is not significant, and there is no significant step change when requiring a 25-year (or longer) length.

In the

maybe camp, the cubic spline analysis is certainly suggestive of a significant change, just barely falling into the no trend camp (using a 95% confidence interval).

While this analysis is perhaps not satisfying from a community planning perspective, since "maybe" seems like it's not an "actionable" answer, from a climate perspective it is interesting that we are close to being able to detect an increase, which for precipitation in Alaska is not (yet) usually the case. However, increasing precipitation during the 21st century is exactly what the the climate model consensus have for nearly all of Alaska, and we

may be starting to see that reflected in Fairbanks. The next several years will help to clarify the trend for the early 21st century.