Objective Comments and Analysis - All Science, No Politics

Primary Author Richard James

2010-2013 Author Rick Thoman

Wednesday, December 27, 2023

Cold At Last

Wednesday, December 20, 2023

AI Forecast Follow-Up

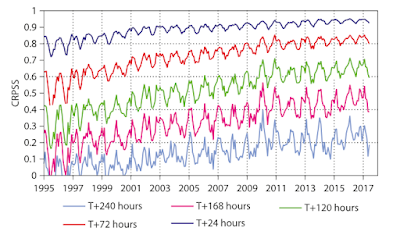

Last month I penned a few comments on the big news in the weather industry: the emergence of AI models as a legitimate competitor to traditional physics-based models for weather forecasting.

To provide a more concrete example of the impressive performance of the new models, I pulled out forecasts for Fairbanks from two of the AI models that I've been running over the past couple of months. Note how remarkable this is: the models can be run on pretty modest hardware; you don't need a supercomputer.

Here's a basic comparison of forecast skill for days 1-14 of the 2m temperature forecasts for Fairbanks (click to enlarge). Here I'm using ERA5 reanalysis data as "ground truth".

The two AI models are GraphCast (Google) and FourCastNet (NVIDIA), and I'm running FourCastNet with 50 members based on the initial conditions in the ECMWF ensemble forecast. GraphCast is more computationally demanding, so I only have a single member each day. The usual (traditional) ECMWF and GEFS ensembles have 51 and 31 members respectively.

Remarkably, GraphCast's single forecast member equals the ECMWF ensemble skill out to 9 days. The ECMWF ensemble is the gold standard for medium-range forecasting, so this is a terrific result that confirms the power of the new models. In contrast, FourCastNet starts out strong but roughly equals GEFS after 5 days, with inferior skill. Note that systematic bias could affect these results to some extent, as I used the ERA5 seasonal normal as the baseline, without any bias correction.

Looking at the mid-atmosphere 500mb height forecasts, it's interesting to note that GraphCast drops off significantly after 10 days, while FourCastNet shows a very strong performance. This may be reflecting the benefit of an ensemble approach for the medium-range (7-14 day) forecast.

More results will be forthcoming when I have time. In the meantime, here's the latest forecast I have access to: the message is "warmer than normal" in Fairbanks, and perhaps especially around Christmas Eve and New Year's Eve.

The CPC's 8-14 day forecast also calls for warmth for central and eastern Alaska around the New Year period. It's a very typical El Niño pattern nationwide.

Thursday, December 14, 2023

Stormy Weather

The last few days have brought wild weather to large parts of Alaska, courtesy of a very powerful upper-level trough and associated low pressure system over the northern Gulf Coast. Anchorage received measurable snow for 7 days in a row, with a total of almost 20", and that's enough to put them in first place for season-to-date snowfall at this point in the year.

Not surprisingly, the surface pressure analysis on Tuesday afternoon looked very similar to that from about a month ago, when Anchorage received its really big snow storm: the low center was a hundred miles or so to the southeast of the city.

Compare to the November 9 map posted here:

https://ak-wx.blogspot.com/2023/11/south-coast-snowstorm.html

The 500mb map from the same time on (this) Tuesday afternoon shows the mid-atmosphere trough in all its glory:

The eastward "tilt" of the trough at lower latitude is characteristic of particularly strong storm systems with a lot of upper-level "energy". The sub-500 dm height at Anchorage (499dm to be precise) is notably low: about a third of winters in recent decades haven't seen a 500mb height that low all winter.

Here's an estimate of 3-day total liquid-equivalent precipitation, and the second map below indicates the estimated return frequency: over 5 years in parts of the higher terrain from the northern Panhandle up towards the Alaska Range.

The Fairbanks area received a significant snowfall, with a surprisingly large precipitation total of 0.54" (liquid equivalent) in the last 2 days (Tuesday and Wednesday). I say "surprisingly" because temperatures were fairly low, only peaking at 10°F and 7°F on the two days respectively, and the snow:water ratio was an unusually low 11:1. About 50% of winters in Fairbanks don't see a single 2-day precipitation event as large as this - although it has become more common in recent years.

Finally, the big pressure gradients associated with the broader circulation anomaly also generated big winds, especially for the West Coast, where the winds were northerly and created blizzard conditions. Here are peak wind gusts (mph) for Monday and Tuesday.

Sadly the weather appears to have been a contributing factor in the deaths of two Nome residents on Sunday night:

Friday, December 8, 2023

Warm November and El Niño

Saturday, December 2, 2023

Hythergraphs

Monday, November 27, 2023

AI Weather Forecasts

Tuesday, November 21, 2023

Wild Weather in the South

Weather is never very far from the news in a place as big as Alaska, and the more extreme events aren't usually good news. Yesterday a major Gulf of Alaska storm barreled into a cold air mass and high pressure over southern Alaska, and the results were dramatic: damaging winds in the Matanuska Valley, and a major landslide down south in Wrangell. Sadly the landslide brought loss of life, and perhaps worse than the 2020 Haines landslide.

ADN news links:

The rain in the Southeast doesn't appear to have been particularly unusual for the region; the map below shows 72-hour totals (click to enlarge). But it was pretty wet earlier in the autumn, so there may have been a compounding risk. Sitka is in the top 10 for rainfall since September 1.

As for the winds around Palmer and Wasilla, the map below shows how localized the wind storm was in the greater Anchorage area (showing yesterday's peak gusts in mph).

Thursday, November 16, 2023

A Few Notes

A few comments on various topics. First, the snow onslaught in Anchorage: the recent 10-day total of 38" amounts to the 3rd highest on record. Last year's December snow was even a bit greater, and the top event was back in February 1996.

It's really remarkable to see such a large amount of snow at the airport - where there is typically less snow than across most of the area - and in back-to-back years. With La Niña last winter and El Niño this winter, we can't pin the blame on similar climate forcing, so perhaps it's just "luck of the draw".

Second, the Tanana River at Nenana froze up last week on Wednesday the 8th. The scene is suitably wintry today:

But the mighty Yukon River hasn't frozen over at Dawson yet; here's the latest video from the webcam:

The situation at Dawson looks about the same as last year at this time:

https://ak-wx.blogspot.com/2022/11/historical-context-for-warmth-freeze-up.html

Long-time readers will recall discussion of the lack of a proper freeze-up all winter long at Dawson in some recent years:

https://ak-wx.blogspot.com/2020/02/yukon-frozen-at-dawson.html

This autumn has certainly been on the warm side of normal in Dawson, but it's not breaking records for lack of freezing potential: here's a chart of accumulated freezing degree days (accumulated temperature differential below 32°F):

This is from the reliably-reporting "LRP" site in Dawson, not the airport, where many observations are missing. The city does have a much longer history of climate observations, of course, but it seems there are some discrepancies between the different climate sites that would affect any long-term trend analysis.

And finally, I'll highlight the remarkable lack of sea ice along Alaska's west coast at this time, related to persistent southerly winds and warmth. Rick Thoman posted a graphic to illustrate:

"Sea ice concentration analysis for Wednesday and the same date last year from the National Weather Service Alaska Region Sea Ice Program. Much less ice in the southern Chukchi and Bering Seas currently than this date last year. November 15 and effectively no ice in Kotzebue Sound is especially shocking, even by recent norms."

https://mastodon.social/@AlaskaWx@alaskan.social/111417939896937766

Here's a longer archive of November 15 analyses, from 2021 (top) to 2018 (bottom):

Friday, November 10, 2023

South Coast Snowstorm

Tuesday, November 7, 2023

October Climate Data

Rick Thoman has a nice write-up of October's Arctic and Alaska climate anomalies here:

https://alaskaclimate.substack.com/p/october-2023-climate-summary

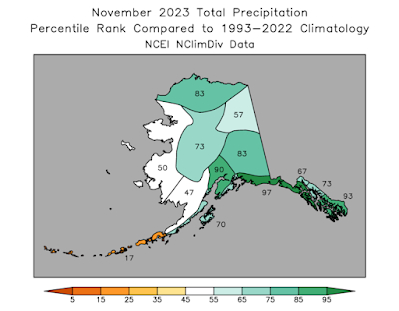

The precipitation contrasts across Alaska were striking: it was much drier than normal for the time of year in the southwest and south-central, but the North Slope and eastern Alaska were notably damp. Rick notes that the Utqiaġvik CRN site measured 1.68" of liquid-equivalent for the month - the highest on record there for October (at either the CRN site or the much longer Barrow/Utqiaġvik climate site). It's also the fourth consecutive month with more than an inch of precipitation at the CRN location.

Snowfall was also relatively abundant in eastern Alaska: as high as 19" in Tok and 17" in Eagle. Also 18" on Keystone Ridge outside of Fairbanks.

Here's a look at snow water on the ground at 5-day intervals through the month, expressed in terms of historical percentile, and estimated by the ERA5 model:

The snowpack was established on October 6 in Fairbanks (considerably earlier than normal), but very little snow remained by the end of the month in the southwestern quadrant of the state. The last week of the month was very mild, but chilly weather earlier in the month allowed for a near-normal monthly average temperature for much of the interior. The Aleutians, North Slope, and Southeast were notably warmer than normal, however.

As for wind, October was relatively calm for the southwest and south-central, but windier than normal in the north and northeast.

Here's the mid-atmosphere pressure pattern that contributed to the surface climate anomalies: the ridge over southwestern Alaska explains the dry and calm weather there.

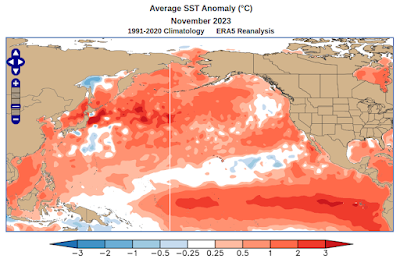

Sea surface temperatures remain much higher than normal in the western Bering Sea and northwestern North Pacific, so we can expect that winds from that direction will tend to bring unusually mild conditions to Alaska in the coming months.

Given that we have a strong El Niño in play this winter, which tends to produce a strong Aleutian low and frequent southwesterly flow across Alaska, I'd say the chances of a very mild winter are much higher than normal. NOAA's Climate Prediction Center agrees:

For a comprehensive discussion of the winter outlook, check out Rick Thoman's November 17 presentation here:

https://uaf-accap.org/event/nov-climate-outlook/