Deep southerly flow aloft continues to transport very warm air northward across Alaska, although the proximity of the upper-level ridge has allowed valley-level locations in the central and eastern interior to cool off recently. Western areas are having no such luck; for example, Kotzebue has had 8 straight days with a high temperature at or above 32°F (including today). This is an all-time record (1930-present) for the winter months of December through February (the previous record was 6 days on several occasions). McGrath is at 9 days and counting with a high temperature of 35°F or higher, which is also an all-time record.

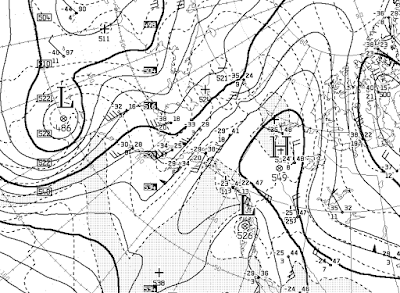

Here's this morning's 500 mb analysis, courtesy of Environment Canada; it's clear that the air now affecting Alaska was located far to the south not many days ago.

Temperatures above freezing have been reported at many mid-elevation locations on both sides of the Brooks Range in the past day or so. For example, the Ivotuk CRN site at 1900' elevation remained mostly above freezing for a lengthy period yesterday, as shown in the following chart.

The nearby Howard Pass RAWS (2062'), notorious for its frequently severe wind chill, was also above freezing at times yesterday:

Farther to the east, Toolik Lake (2493') also experienced a thaw in the early hours of yesterday.

Other high temperatures include 35°F at the Imnaviat Creek SNOTEL (3050'), 38°F at the Sagwon SNOTEL (1000') on the North Slope, and 34°F at the Coldfoot SNOTEL (1040') on the south side of the Brooks Range.

Even Umiat, at low elevation on the banks of the Colville River, rose to 32°F yesterday evening. This is not unprecedented, but certainly very unusual.

1. How often do we get this type of weather regime that produces such southerly flow? Are we getting such flows more often?

ReplyDeleteI guess one rough way to get this is to use the pressure difference between Koztebue and Fairbanks to measure the approximate position of the ridge.

2. Since ridges in winter are cold and ridges in summer are hot, what happens in the transition period of fall and spring?

3. This current ridge where it is positioned is more like summer. Is this a coincidence?

Eric...

Delete1. It's a common pattern and certainly very common in the past couple of years. I like your idea of measuring the west-east gradient.

2. I would say that ridges in winter are cold only up to a point; they create strong inversions, which means cold at the surface, but on the west side of the ridge the overall air mass is warm, so it might not be colder than normal at the surface. But in general, yes - and spring and autumn fall in the middle, with the outcome depending largely on whether there is snowcover.

3. Good observation; this is related both to El Niño, with extensive low pressure in the North Pacific, and a recent change to rising pressure in the Arctic basin (negative AO phase).

Thanks, Richard.

DeleteYour response to point 3 has made me wonder how the varying strengths of Pacific and Arctic pressures affect the positions of ridges over Alaska. If the current ridge is more easterly because of higher pressure over the Arctic and lower in the Pacific, would that mean that if the pressures were reversed that the ridge would be more over Alaska - like a more typical winter? Obviously, the ridge over Canada is going to warm up Alaska more than if over western Alaska. I would also think that it would influence the strength of the Aleutian Low and subsequent ice formation along the western Alaskan coast.

I was thinking more of the northerly position of the ridge, rather than an eastward displacement. However, La Niña tends to favor a ridge in the Bering Sea and thus cold for Alaska, so there's certainly a connection there in terms of the preferred longitude of ridging.

Delete