Alaska's wildfire season continues to go from bad to worse in a big way, with today's AICC report stating that fire acreage has reached nearly 2 million acres statewide.

Smoke has been bad in many places and downright hazardous for some. Amazingly, even Nome reported visibility down to a quarter of a mile in smoke yesterday, despite the big fires being hundreds of miles away to the southeast. Looking at Nome's historical data, there don't seem to be any historical instances of visibility as low as 0.25 miles from smoke alone (i.e. without fog).

In Fairbanks there were 13 days in June with smoke and visibility of 6 miles or less, and 10 days with visibility of 2 miles or less - both records for the month. Only 3 calendar months in Fairbanks have had more days in the 2-mile-or-less category of bad smoke: the Augusts of 1957, 2004, and 2005. However, there's still a long way to go before conditions get as bad as those years: summer 2004 had 18 days with 1-mile-or-less visibility, and 12 days with 0.5 miles or less.

What's to blame for the extreme fire activity? Several ingredients are involved. First - obviously - extreme dryness, which continues with no significant relief. Here are the latest 30-day percent of normal precipitation map, and the latest Drought Monitor analysis for Alaska:

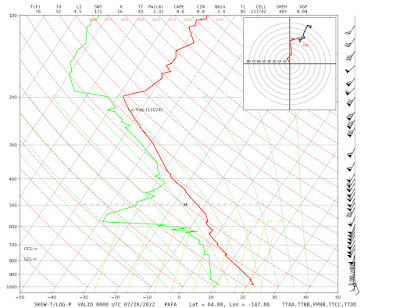

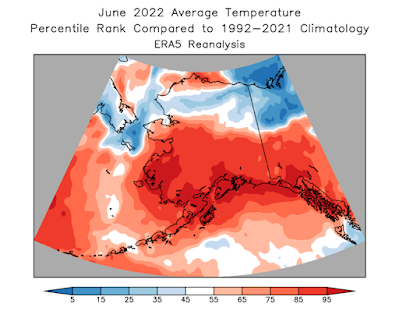

Second, unusual warmth. Courtesy of Rick's Twitter feed, here are the June temperature departures from normal.

Third, enhanced drying of fuels from low humidity, abundant sunshine, and perhaps above-normal wind (to be confirmed in a few days when the June ERA5 analysis is available). According to the NIFC fire outlook yesterday, "Fuels are already extremely dry, with fire danger representative of deeper duff layers near record highs in parts of the state. This indicates that even the mid and deeper layers are burnable, so fires will burn hotter, more completely, and will endure even moderate rain events. Fuels this dry are very resistant to control efforts."

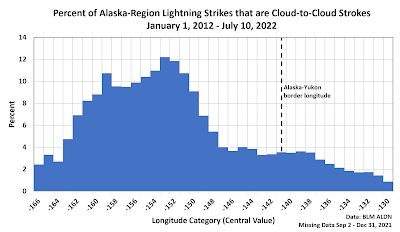

Finally, lightning: despite the dryness, there have been about 54,000 lightning strikes so far this year in Alaska, which is only a little behind normal according to the 2012-present history of the current detection system.

I think it's also clear that this year's situation is not just a confluence of unusual short-term circumstances; it also illustrates how the long-term warming trend has made it easier to develop extreme dryness when rainfall is absent. Consider the following chart of May-June average vapor pressure deficit from Bethel, based on hourly data since 1950.

A "normal" year for evaporation in the past two decades would have been significantly above normal prior to 1980, and this year's May-June VPD was the highest on record. When combined with the severe rainfall deficit (4th lowest on record for Bethel, 1924-present), it's easy to see why fuel dryness has become extreme.

Here's the write-up from yesterday's NIFC wildland fire potential outlook.

Alaska: Above normal fire potential is expected for much of southwest, south central, and Interior Alaska July through August. All other areas will be normal, with normal potential forecast across Alaska September into October.

A month of hot and dry weather across much of the state has led to extremely dry fuels across the landscape. Temperatures in the 80s, relative humidity below 25%, and periods of very gusty winds have exacerbated this typically dry month Precipitation has been minimal, with even the localized convective showers typical of June largely absent. The US Drought Monitor has much of southwest, south-central, and the western and central Interior Alaska as abnormally dry with areas of moderate drought. The drought correlates well with current fire weather and fuel indices.

Warm and dry weather is forecast for the central and eastern Interior for the next few weeks, with the chance for afternoon showers and thunderstorms most days. Southwest Alaska will see some moderating weather, but several days of rain with total accumulation near an inch is needed to stop fires there. Therefore,an end to the fires there seems unlikely currently. In addition, south-central Alaska is extremely dry, and any emerging fire could quickly become significant.

There are numerous fires in the southwestern and central Interior. Though some are burning in limited fire management areas, many are burning in areas that need point protection and resource commitments. Many of these fires will likely need attention until September when freezing weather returns. With the focus of hottest and driest weather shifting to the eastern half of the state, the next month is expected to have above normal significant fire activity.

Alaska Predictive Services has issued a Fuels and Fire Behavior Advisory for southwest Alaska and much of the Interior. During July, daylight hours are long, and the sun angle is high, so solar heating continues to cause drastic warming and drying of fuels. Fuels are already extremely dry, with fire danger representative of deeper duff layers near record highs in parts of the state. This indicates that even the mid and deeper layers are burnable, so fires will burn hotter, more completely, and will endure even moderate rain events. Fuels this dry are very resistant to control efforts.

Alaska’s high latitude and boreal forest make it one of few places that can have a record snowpack and late snowmelt immediately followed by one of its busiest fire seasons. Though the summer started out cool with little to no fire activity, it quickly turned very hot and dry. With a lot of fire on the ground and more ignitions imminent during the climatological peak of lightning into early July, the fire season in Alaska will continue to be extremely busy. Even if end-of-season rains arrive on time by mid-August, these fires will need constant attention through the end of August. By September, it is likely that cooler weather, lower sun angle, and limited daylight will bring the season to a close and back to normal conditions.