A couple of interesting items came to my attention today. First, the Yukon appears to be properly frozen over at Dawson City in the Yukon:

This is big news over there, because the lack of freeze-up next to town has been a huge problem in recent years; freeze-up has often been much delayed and sometimes hasn't occurred all winter. I've commented on it occasionally, most recently last March:

The change this year isn't caused by colder weather - it hasn't been unusually cold - and the lack of freeze-up in recent years was generally not caused by unusual warmth. When I have a chance, it will be worth looking at regional streamflow and precipitation data from recent months to see if anything stands out.

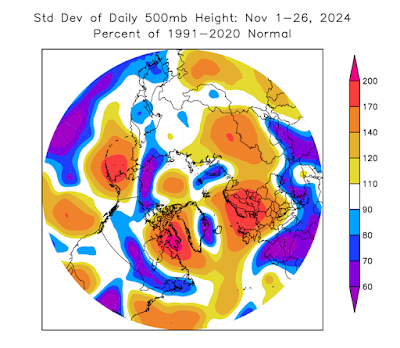

On a completely different note, I ran some calculations today to establish whether the Northern Hemisphere circulation patterns have been unusually volatile this month; it sure seems like it. The answer is yes: the following chart shows a metric of 500mb volatility for 45-90°N around the globe.

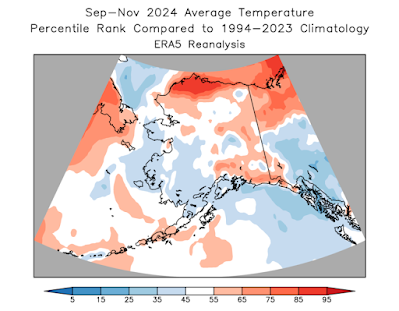

To be precise, the figure shows the area-average of the standard deviation of 500mb heights for November 1-26, expressed as a fraction of the 1991-2020 normal (which differs from place to place). Here's a map of the departure from normal: 500mb heights have been much more variable than normal over the eastern Bering Sea and southwestern Alaska, as well as near Baffin Island and over northern Europe.

The region of high variance near Alaska largely reflects the dramatic change from this a few weeks ago:

to this last week:

The big ridge over the eastern Aleutians and southwestern Alaska about a week ago was bumping up against records for the month of November.

What could explain the volatile patterns around the higher latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere? I think it's the unusual combination of sea surface temperature anomalies across the tropics and the mid-latitude oceans. We have a weak La Niña, which tends to favor meandering "blocking" patterns in the high latitudes in early winter (November in particular), but we also have tremendous warmth in the northwestern North Pacific, which favors mid-latitude ridging (high pressure) and a stronger, more west-east jet stream to the north of the ridge. These two Pacific ocean anomalies therefore currently have opposing influences on the jet stream pattern, as I see it, and volatility has resulted.

Looking ahead, as winter settles in, La Niña's influence will very much shift towards favoring a stronger jet stream with a strong polar vortex, and that in turn will tend to favor unusual cold in Alaska, particularly in the south. This is very consistent, of course, with a negative PDO phase, which is locked in because of the warmth to the east of Japan. Here's the SST anomaly from the past month:

In conclusion - bundle up; and happy Thanksgiving to U.S. readers.