My post about the Fairbanks spring flood of 1948 elicited a comment from reader Andy, who suggested that cold in the second half of April might be a more significant indicator of breakup flooding than unusual cold earlier or later in the spring. It certainly played a role in the 1948 flood: April 16-30 was by far the coldest in Fairbanks history. More recently, 2013 saw a very cold April, and breakup was record late with a near-record peak discharge on the Tanana River.

I decided to take a look at this more closely using discharge data from the Chena River in Fairbanks. Peak discharge isn't the same thing as breakup flooding, because the worst floods are caused by ice jams, but discharge gets at the runoff/meltwater part of the problem.

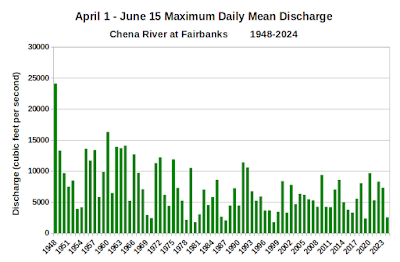

Here's a chart of the peak daily mean discharge in Fairbanks between April 1 and June 15:

Importantly, the Chena River Flood Control Project was completed in 1979, so the peak flows in Fairbanks have been constrained since then.

The flow typically peaks in May, but there is great variability in the date of peak discharge. There's a long-term trend towards earlier peak flow, including since 1980; it has become unusual to see peak discharge after May 15 in recent years, but it used to be common.

This year we're seeing a secondary peak as a heavy snowpack is still melting out on the higher hills:

I chose June 15 as the cutoff date for "spring" discharge because that's when the flow is typically minimized prior to its gradual increase through summer; the weather gets wetter in interior Alaska as summer advances.

With all of this as background, I looked at the correlation between the peak discharge and the average temperature in Fairbanks for 15-day intervals throughout the spring. Here's the result:

The negative correlation indicates that colder conditions correspond to higher peak discharge, which is what we expect: snowmelt is delayed and then occurs more rapidly once the inevitable warmth arrives. In contrast, unusual warmth allows meltout to get under way early, increasing the window of time for all that meltwater to traverse the drainage basin.

Interestingly, there's no obvious date window that is particularly linked to peak flows, and in fact the greatest correlations are found quite early: late March into early April. However, the correlations are quite small, so temperature in these 15-day windows does not explain much of the variance in peak discharge.

The potential relationship of temperature with discharge is somewhat confounded by the influence of snowpack depth: greater snowpack implies higher discharge, and spring snowpack is also correlated with temperature. Not surprisingly, there is quite a good relationship between peak snowpack water content and peak discharge; the following chart uses snow water equivalent data from five SNOTEL sites in the hills above Fairbanks.

Using this relationship, we can remove the linear effect of the snowpack on the peak discharge, leaving us with the "residual" discharge that can't be explained by snow water content. If we then compare the residual discharge with temperature, the correlations are a bit different:

This result suggests that temperatures in early spring (March 15-April 15) are actually more significant for determining peak discharge than temperatures in late April and early May. I find this a bit hard to believe, because late March temperatures still average well below freezing in the Fairbanks area, so even warm years wouldn't be expected to see significant meltout that early in the season. But perhaps there are still other correlations involved; warmth in late winter tends to occur with dry, sunny, and perhaps windy weather, and it's certainly true that humidity, sunshine, and wind can affect snowpack.

As for the larger correlation that shows up in early-mid May, this is right around the average time of peak flows, but at that time I would expect cold weather to actually reduce flows as the latter part of meltout slows down. Again, perhaps the relationship - which is not particularly strong - is confounded by other factors.

I would be interested to hear any suggestions on how to refine the analysis in order to gain more insight.